Most syndicated loan deals in the market today have loopholes in their documentation that make the credit agreements look like Swiss cheese rather than buttoned-down debt contracts. Aggressive law firms have used creative interpretations of these loopholes to enable lenders with majority positions in syndicated debt to leverage their position at the expense of minority holders. When loans become distressed and borrowers face potential bankruptcy, the majority holders capture the bulk of the recovery pie, leaving only crumbs for minority creditors. Within the industry these tactics are known as lender-on-lender violence, or more euphemistically, Liability Management Exercises (LME). These maneuvers present a significant challenge to the broadly syndicated loan (BSL) market, and the menace is growing by the day, as more companies struggle under the burden of elevated interest rates.

Lender-on-lender violence explained

There are a variety of legal stratagems used to execute these LMEs, but the endpoints are all the same—an inequitable distribution of the pie. Put simply, when a loan is distressed and facing default, lenders can collude to establish a majority. With a voting majority in place, and aided by sophisticated lawyers, these lenders can change the rules of the road to take the lion’s share of any debt recovery for themselves, leaving the minority out in the cold. For example, imagine a loan syndicate with say 40 members. If a subset of those members come together to collectively hold 50.1% of outstanding debt, they now have a dominant position and can exercise outsized influence. Keep in mind, this cartel can consist of as few as 4-5 lenders with chunky positions, as the majority is determined by dollar amount, not lender count. Now that they are in the driver’s seat, they can amend the loan document with a simple majority vote and self-deal preferential returns for themselves.

Historically when a company would default—and let us assume a recovery rate of 60 cents on the dollar—that 60 cents would be shared pro rata among all lenders who have suffered. In the brave new world of lender-on-lender violence, this is no longer the case. The 50.1% syndicate majority could theoretically take 50 cents for themselves giving them a full recovery, and leave 10 cents for the 49.9% minority, resulting in a 20% recovery for this hapless group of lenders.

These loopholes have always existed, but the spirit of loan agreements was to share in any recovery on a pro rata basis. However, over the last few years, a small coterie of law firms have increasingly pushed the envelope and exploited the convoluted verbiage in debt documents. Aggrieved lenders have sued in court to fight back against some of these moves, but the trials take time, and a company facing bankruptcy could lose all its value before the courts settle the matter. In many instances, the lenders capitulate and accept the unjust outcome, rather than spend more time and money on lawyers.

The management teams of distressed companies, which are often acting on the direction of their private equity sponsors, are not blameless in this cycle of lender-on-lender violence. They are only too eager to abet the infighting among lenders, in the hopes of getting some financial advantage for themselves. When the equity owners are dealing with a potential bankruptcy, they are looking down the barrel of a complete wipeout, as they will theoretically have to be zeroed out before the lenders take the first dollar of loss. To avoid this, they can collude with the majority lender group to effectuate various kinds of subterfuge in exchange for some payout. This Faustian bargain can have various permutations. One popular flavor includes moving valuable assets outside the reach of all the lenders and giving the majority lender group that juicy collateral. In exchange, the lenders will pump in some new cash that will extend the runway of the company, giving the management team some option value (which is better than the wipeout they were facing in a bankruptcy).

A rose by any other name

These maneuvers have names. In the same way brand names like Band-Aid, Thermos, and Chapstick have become verbs in the marketplace, the company associated with the first execution of a particular kind of maneuver is identified with it. Names like J. Crew, Serta Simmons and Chewy are used eponymously in the industry, reflecting the legal strategy employed. These strategies include things like priming, up tiering, and drop-down transactions. We won’t bore you with the details, but suffice it to say these are complex maneuvers, using abstract structures and aggressive interpretations of documents. The goal is to benefit a majority group of creditors over a minority. So, when new syndicated deals are made today, parties will explicitly say they want Serta Simmons protection, J. Crew protection, and so forth. The problem is that while newer deals may have closed these loopholes, they remain active in older deals. These older deals still represent the bulk of the market.

Another challenge is that no matter how sophisticated contracting parties may be, the law firms at the vanguard of liability management exercises are usually a step ahead. You can plug all the known holes in the document, but the handsomely compensated lawyers on the other side will find new chinks in the armor.

Bear in mind, these contracts are exceptionally voluminous. The J. Crew credit agreement was 101 pages and over 87,000 words long. Section 7.02 of the document—the part that the minority group of lenders came to regret—listed twenty-one permitted investment carve-outs, thirty-two cross references to other sections, and forty-four defined terms.1 Good luck cinching the loopholes.

A Prisoner’s dilemma

An interesting dynamic in these legal wranglings is that the lenders are forced to confront the classical “Prisoner’s Dilemma.” In the canonical game-theory scenario, two suspects are arrested and interrogated separately for a crime. Each prisoner has two choices: cooperate with the other prisoner (remain silent) or betray the other prisoner (confess). Each does not know what the other is doing. If both prisoners cooperate (remain silent), they receive a moderate sentence. If one prisoner betrays (confesses) while the other cooperates, the betrayer goes free, and the cooperator receives a harsh sentence. Due to uncertainty and incentives, it is always the dominant strategy for a prisoner to betray the other. The game illustrates a common scenario where individuals’ rational decisions lead to outcomes that are not optimal for the group.

It is not a perfect parallel, but as it pertains to LME, we can imagine the lenders in a loan syndicate as prisoners faced with a similar dilemma. They can cooperate with other lenders and maximize value for all parties, or they can betray the other lenders, thereby ensuring the best outcome and highest return for themselves. Constrained by a lack of knowledge of what others in the syndicate will do, coupled with an implicit economic interest in capturing the best possible outcome, the lenders will most certainly choose to betray other members of the syndicate, and quickly. First movers will have an advantage; the faster they join a group seeking debt majority, the higher the likelihood they will receive a larger piece of the recovery pie. The alternative—that is sticking together—would be irrational, given they know that it is completely rational for other players in the syndicate to J. Crew (rhymes with something else) them first.

The broadly syndicated loan market lends itself to this sort of activity. First and foremost, the syndicates are made up of large pools of lenders—30 to 50 for the bigger facilities. This results in party anonymity. If you thought it was easy for the cops to get one of the two prisoners in our example to break, imagine how easy it would be for the borrower (“the cops”) to peel off a couple of lenders from a 40-person group of lenders.

Additionally, syndicated loans are tradeable. Large firms with lots of expertise can vulture in after a loan has already fallen into distress, buy up positions for pennies on the dollar, and deliberately engineer these shenanigans to maximize their profit.

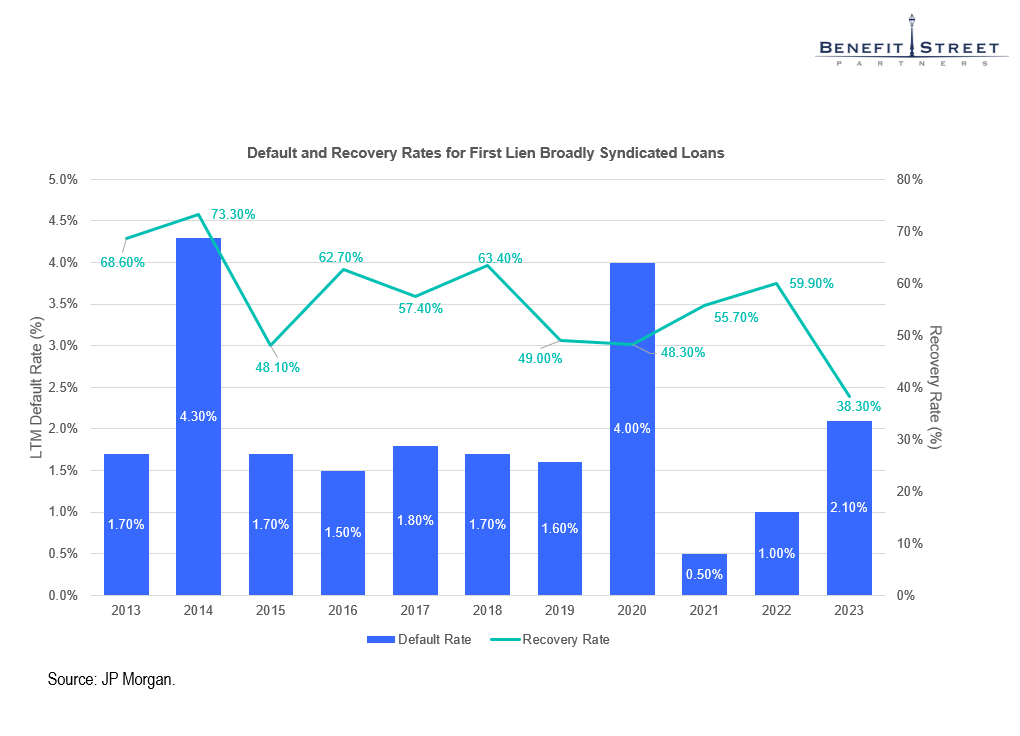

Given the increased frequency of LME in the broadly syndicated market, recoveries rates for syndicated loans have been trending lower recently (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Recoveries are Likely to be Lower for Syndicated Loans in the Future

Direct Lending bucks the trend

Fortunately for investors in the direct lending market, these types of tactics have not gained the same traction. Direct lending deals are characterized by contracts between a single lender (or a small club of lenders) and a borrower, versus 20 to 50+ lenders in the broadly syndicated market. These deals are negotiated bilaterally, and as a result usually have much stronger covenant protections and fewer loopholes.

Furthermore, direct lenders prioritize building long-term relationships with borrowers, focusing on growing along with the company. In most cases, the lender makes an initial loan and then a series of follow-on incremental loans as part of the same deal, to help the borrower grow and meet its needs for more capital. This relationship-centric, repeated interaction fosters cooperation and mitigates the risk of adversarial action from the borrower. It is much easier for the borrower to burn bridges with a sea of faceless lenders in the broadly syndicated market, many of whom they may never interact with again, versus ruining a relationship with a handful of direct lenders who will be vital sources of capital in the future.

The prisoner’s dilemma scenario is not applicable in many direct lending deals as there is often only one lender (the prisoner isn’t going to betray himself!). But even if we consider a direct lending deal with a small club (3-5 lenders), choosing to betray a fellow lender is not economically rational. Private debt is a small, close-knit community. Firms are familiar with each other and conduct business together regularly. If the metaphorical cop (the borrower) were to come to one and suggest they turn against the other for a short-term gain, it’s highly unlikely to succeed. Instead, the prisoners (or lenders) would work together and remain silent, assuring the best optimal collective outcome for the group. Each would get an equitable piece of the proverbial pie. This is precisely what game theory would predict for a game with the possibility of coordination and repeated interaction. This is what is happening in the direct lending market. In the broadly syndicated loan market, not so much.

Definitions

Broadly syndicated loans (BSLs) are a form of financing where a syndicate of lenders work together to provide a large loan to a single borrower.

Direct syndicated loans (DSLs) are a type of syndicated loan where the syndicate of lenders provides funds directly to the borrower without the use of an intermediary or arranger.

A first lien refers to the legal right of a creditor to be the primary claimant against the assets of a borrower if the borrower defaults on the loan. This means that in the event of a default, the holder of the first lien has the first priority to seize and sell the borrower’s assets to recover the owed amount.

A second lien is a type of debt that is subordinate to a first lien, meaning it has a lower priority in terms of repayment in the event of a borrower’s default or asset liquidation. If a borrower defaults, any second-lien debt gets paid only after the first or original first lienholder is paid off.

Liquidity refers to the degree to which an asset or security can be bought or sold in the market without affecting the asset’s price.

A syndicated loan is a loan offered by a group of lenders (called a syndicate) who work together to provide funds for a single borrower.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Equity securities are subject to price fluctuation and possible loss of principal.

Fixed income securities involve interest rate, credit, inflation and reinvestment risks; and possible loss of principal. As interest rates rise, the value of fixed income securities falls. Changes in the credit rating of a bond, or in the credit rating or financial strength of a bond’s issuer, insurer or guarantor, may affect the bond’s value. Low-rated, high-yield bonds are subject to greater price volatility, illiquidity and possibility of default.

Investments in many alternative investment strategies are complex and speculative, entail significant risk and should not be considered a complete investment program. Depending on the product invested in, an investment in alternative strategies may provide for only limited liquidity and is suitable only for persons who can afford to lose the entire amount of their investment. An investment strategy focused primarily on privately held companies presents certain challenges and involves incremental risks as opposed to investments in public companies, such as dealing with the lack of available information about these companies as well as their general lack of liquidity.

Diversification does not guarantee a profit or protect against a loss.

Any companies and/or case studies referenced herein are used solely for illustrative purposes; any investment may or may not be currently held by any portfolio advised by Franklin Templeton. The information provided is not a recommendation or individual investment advice for any particular security, strategy, or investment product and is not an indication of the trading intent of any Franklin Templeton managed portfolio.

IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realized. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Issued in the U.S.: Franklin Resources, Inc. and its subsidiaries offer investment management services through multiple investment advisers registered with the SEC. Franklin Distributors, LLC and Putnam Retail Management LP, members FINRA/SIPC, are Franklin Templeton broker/dealers, which provide registered representative services. Franklin Templeton, One Franklin Parkway, San Mateo, California 94403-1906, (800) DIAL BEN/342-5236, franklintempleton.com

Canada: Issued by Franklin Templeton Investments Corp., 200 King Street West, Suite 1500 Toronto, ON, M5H3T4, Fax: (416) 364-1163, (800) 387-0830, www.franklintempleton.ca

Offshore Americas: In the U.S., this publication is made available only to financial intermediaries by Franklin Distributors, LLC, member FINRA/SIPC, 100 Fountain Parkway, St. Petersburg, Florida 33716. Tel: (800) 239-3894 (USA Toll-Free), (877) 389-0076 (Canada Toll-Free), and Fax: (727) 299-8736. Distribution outside the U.S. may be made by Franklin Templeton International Services, S.à r.l. (FTIS) or other sub-distributors, intermediaries, dealers or professional investors that have been engaged by FTIS to distribute shares of Franklin Templeton funds in certain jurisdictions. This is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to purchase securities in any jurisdiction where it would be illegal to do so.

Issued in Europe by: Franklin Templeton International Services S.à r.l. – Supervised by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier – 8A, rue Albert Borschette, L-1246 Luxembourg. Tel: +352-46 66 67-1 Fax: +352-46 66 76. Poland: Issued by Templeton Asset Management (Poland) TFI S.A.; Rondo ONZ 1; 00-124 Warsaw. South Africa: Issued by Franklin Templeton Investments SA (PTY) Ltd, which is an authorised Financial Services Provider. Tel: +27 (21) 831 7400 Fax: +27 (21) 831 7422. Switzerland: Issued by Franklin Templeton Switzerland Ltd, Stockerstrasse 38, CH-8002 Zurich. United Arab Emirates: Issued by Franklin Templeton Investments (ME) Limited, authorized and regulated by the Dubai Financial Services Authority. Dubai office: Franklin Templeton, The Gate, East Wing, Level 2, Dubai International Financial Centre, P.O. Box 506613, Dubai, U.A.E. Tel: +9714-4284100 Fax: +9714-4284140. UK: Issued by Franklin Templeton Investment Management Limited (FTIML), registered office: Cannon Place, 78 Cannon Street, London EC4N 6HL. Tel: +44 (0)20 7073 8500. Authorized and regulated in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Australia: Issued by Franklin Templeton Australia Limited (ABN 76 004 835 849) (Australian Financial Services License Holder No. 240827), Level 47, 120 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000. Hong Kong: Issued by Franklin Templeton Investments (Asia) Limited, 17/F, Chater House, 8 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong. Japan: Issued by Franklin Templeton Investments Japan Limited. Korea: Issued by Franklin Templeton Investment Advisors Korea Co., Ltd, 3rd fl., CCMM Building, 101 Yeouigongwon-ro, Yeongdeungpo-gu, Seoul Korea 07241. Malaysia: Issued by Franklin Templeton Asset Management (Malaysia) Sdn. Bhd. & Franklin Templeton GSC Asset Management Sdn. Bhd. This document has not been reviewed by Securities Commission Malaysia. Singapore: Issued by Templeton Asset Management Ltd. Registration No. (UEN) 199205211E, Inc. 7 Temasek Boulevard, #38-03 Suntec Tower One, 038987, Singapore.

Please visit www.franklinresources.com to be directed to your local Franklin Templeton website.

1. Source: The Yale Law Journal. “J. Crew, Nine West, and the Complexities of Financial Distress.” November 10, 2021.