US productivity growth accelerated sharply over the course of 2023. Financial markets have been paying close attention to various measures of inflation, wage growth, gyrations in employment and unemployment, and consumer and business confidence. But I think productivity might turn out to be the most intriguing and important economic development and warrants closer attention.

Productivity tells us how much an economy can produce with a given level of resources. Labor productivity, in particular, tells us how much an economy’s workforce can produce given the level of capital stock and technology available. Stronger productivity growth drives faster improvements in per-capita incomes and living standards. It also has an important impact on financial markets—a dollar invested in real economic activity has a stronger return. Other things equal, this should translate in stronger equity market performance.

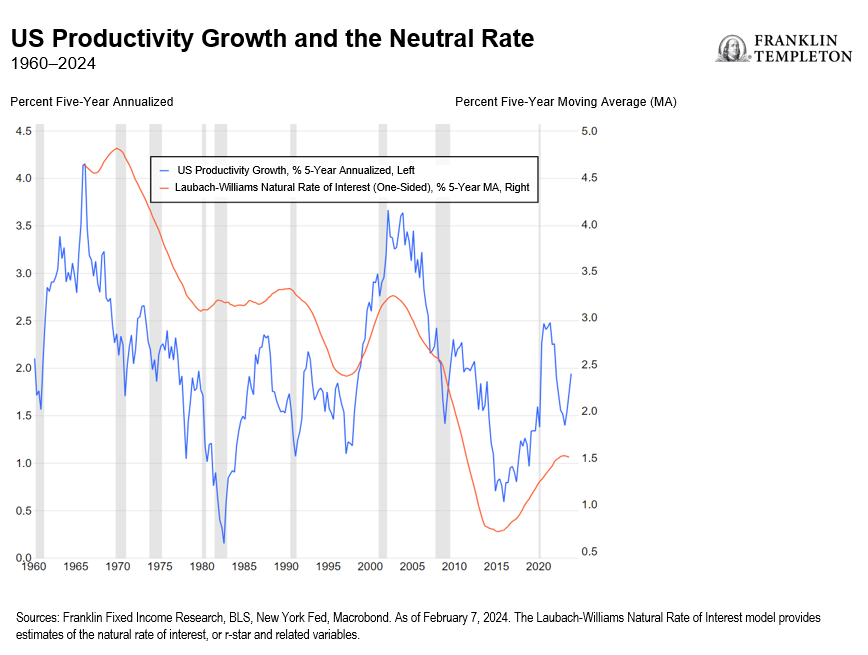

Faster productivity growth also means greater real investment opportunities and a corresponding higher demand for capital, and therefore typically results in a higher equilibrium (or “neutral”) rate of interest, the famous “r*”. This is confirmed by the chart below, which shows a close correlation between productivity growth and the estimated neutral interest rate.

Over the past decade, proponents of the Secular Stagnation hypothesis argued that structurally lower productivity growth would continue to contribute to weak economic growth and permanently low interest rates. This view is still reflected in the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) projections for the long-term fed funds rate at 2.5%, which implies a real neutral rate of just half a percent (in the long-term inflation is assumed at its 2% target).

What’s happening to productivity? Let’s start with the numbers: labor productivity growth (output per hour worked) accelerated from -0.6% in the first quarter of 2023 to 1.2% in the second quarter, 2.3% in the third quarter and 2.7% in the fourth quarter.1 The latter part of last year looks particularly encouraging—annual productivity growth averaged 2% during the last nine months and 2.5% over the last six months.2 To understand what these numbers mean, let’s put them in historical perspective.

During the two decades between 1974 and 1995, US productivity growth averaged 1.5%. Then, between 1996 and 2005, productivity growth doubled to 3%.3 A substantial body of academic research credits the first wave of digital innovation, the so-called Information and Communication Technology (ICT) revolution, as spurring most of this acceleration. Computers made their way through the economy, and companies gradually figured out how to leverage their power to increase efficiency. Then the impact of the ICT wave faded, and productivity growth reverted to a 1.5% annual average during 2006-2022.

Could the productivity growth acceleration recorded in the later part of 2023 represent a turning point, a move toward the 3% rate of that previous golden decade? An important caveat is that quarterly productivity numbers are very volatile; however, I see a few reasons that suggest we should not be too quick to dismiss the latest reading as statistical noise, and should instead follow the data closely:

- While the data are volatile, since 2006 there has been only one other episode where productivity growth accelerated above 2% for two quarters or more: between the third quarter of 2019 and first quarter of 2020. (Abstracting from the post-global-financial-crisis and post-COVID rebounds, where productivity changes were driven by massive swings in employment.)

- The latest productivity acceleration has occurred against the background of an extremely strong labor market. Rather than reflecting layoffs, it’s more likely to represent companies finding greater efficiency in a situation of (more than) full employment, reflected in a slower pace of hiring.

- The past decade has witnessed very impressive advances in new technologies. Even adjusting for the inevitable exaggerations of the hype cycle, there is no doubt that the past 10 years or more have seen an impressive acceleration in technological innovation, particularly under the Industry 4.0 category. It would be surprising if this new wave of innovation did not at some point trigger an acceleration in productivity growth. (I am not even considering the potential impact of generative AI here, as it is way too early for that to start manifesting itself.)

The puzzle that economists have debated over the past 10 years or so is why all this innovation has not resulted in faster productivity growth. Some argue that we are undercounting the value of output, and therefore underestimating productivity, because a lot of the value of digital innovation accrues for free, and hedonic adjustments to do not capture it fully. The classic example is the smartphone, which, though expensive, serves as phone, camera, calculator, navigator, etc. However, several studies indicate this accounts for only a modest amount of “missing” productivity. Others insist that digital innovation amounts to little more than games and ads, with no significant impact on economic growth, but this line of argument, championed most prominently by Northwestern economist Robert Gordon, seems to underestimate the power of the many new technologies being developed and deployed.

A third explanation is that it just takes time. Companies need to figure out how to deploy new technologies, restructure operations, and equip the workforce with new skills. It’s happened before. In 1987, Nobel Prize Economist Robert Solow famously quipped, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” A few years later, productivity growth doubled. There is no guarantee that we’re on the verge of another productivity boom, but it certainly bears watching.

This discussion seems especially relevant as we think of where interest rates are likely to settle after the inflation fight is over. In his latest press conference, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said he expects productivity to slow to its previous trends; however, other Fed officials have voiced a more optimistic view. If productivity growth is in fact rising to a higher sustained pace, the neutral interest rate will be meaningfully higher than what the Fed has indicated so far in its projections, and than what markets expect. An equilibrium policy rate of around 4% would be more realistic than the 2.5% penciled in the Fed’s forecasts, as I have long been arguing. As such, I believe productivity is definitely one variable that bears watching closely.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Fixed income securities involve interest rate, credit, inflation and reinvestment risks, and possible loss of principal. As interest rates rise, the value of fixed income securities falls. Low-rated, high-yield bonds are subject to greater price volatility, illiquidity and possibility of default.

Equity securities are subject to price fluctuation and possible loss of principal.

IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realized. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Please visit www.franklinresources.com to be directed to your local Franklin Templeton website.

___________

1. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. As of February 7, 2024.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.