Originally published in Stephen Dover’s LinkedIn Newsletter Global Market Perspectives. Follow Stephen Dover on LinkedIn where he posts his thoughts and comments as well as his Global Market Perspectives newsletter.

The field is now set for the US 2024 presidential elections, at least as far as the major parties are concerned. President Joe Biden will stand for re-election, while former President Donald Trump will challenge him. Several notable third-party (or “no-label”) candidates will also be on many state ballots and, as the history of US elections shows, they could prove difference-makers in November.

Our aim in this piece, however, is not to offer an assessment of which candidate is likely to emerge victorious, nor which party will hold a majority after the elections in the US Senate or House of Representatives. Rather, our aim is to offer a summary of key policy differences the major parties offer, and to draw broad conclusions about the implications of competing policy outcomes for capital markets this year and next.

Setting the stage

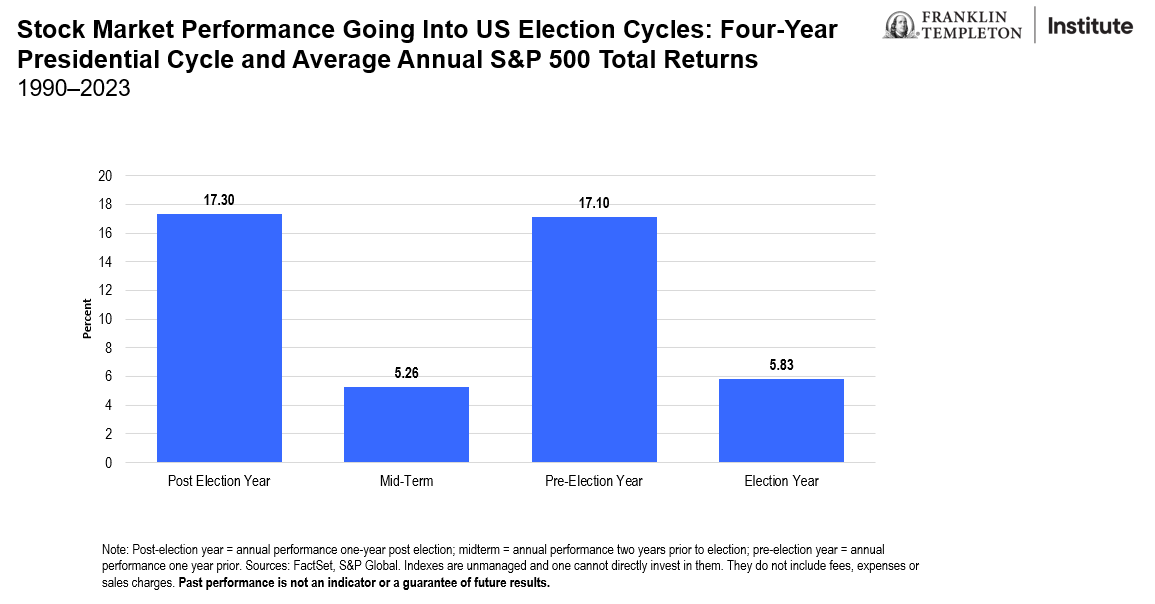

To begin, while we note that both major parties offer seemingly clear policy differences, neither of the presidential candidates has yet to lay out a fully formed party platform. That process typically culminates around the respective party conventions, namely in July (for the Republicans) and August (for the Democrats). Nevertheless, it is possible to highlight likely differences, including those presented in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: Where the Candidates Stand (right click on image to enlarge)

What about divided government?

Presidential power, however, is relatively limited in legislative matters unless majorities in both houses of Congress (i.e., the US Senate and the US House of Representatives) are the same party as the president. And as US politics has become more partisan in recent years, legislation on various issues—including defense spending, appropriations, taxation and immigration—has been stymied by divided government. Accordingly, in many cases platforms may be watered down partly or entirely if the president’s party does not also enjoy majorities in the Senate and House.

In one arena, however, legislation is likely to emerge in 2025 even if divided government in Washington, DC, is the outcome of the 2024 elections. That arena is federal taxation.

The reason is that big parts of President Trump’s signature 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will automatically expire at the end of 2025. Unless legislation addresses this and whoever is president in 2025 signs this into law, taxes will rise for many Americans—an outcome both parties are keen to avoid.

Specifically, most US households will pay higher marginal rates of taxation and enjoy a smaller standard deduction if the TCJA expires unaddressed at the end of 2025. Moreover, the level at which estates will be liable for federal inheritance taxation will halve unless new legislation is passed next year. In contrast, most of the changes to corporate taxation, apart from “bonus depreciation,” will not automatically “sunset” in 2025.

As noted, incumbents in both parties will be keen to avoid hitting many Americans with higher taxes in 2025. Hence, irrespective of how the US election turns out this autumn, we expect that Congress and whoever is president will find a way to extend many, if not all, of the provisions of the 2017 act to at least the majority of taxpayers. Both parties seem to agree that taxpayers with incomes under about US$400,000 would not have their taxes increased.

Budget deficits and interest rates

Unless other taxes are raised, that would mean that the onus of deficit reduction, if any, will fall on spending restraint. Yet without mechanisms to reform the major mandatory programs of Social Security and Medicare, which are among the most popular government programs in both parties, in our view, deficit reduction will be difficult to achieve. That is because mandatory spending, plus interest on the national debt, accounts for over 70% of total federal government spending.1 With the defense budget making up half of the remaining discretionary spending, Congress and the president will be hard-pressed to find the cuts needed to reduce the deficit.

That does not mean, however, that budget deficits must grow as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). They have been falling for the past two years and, barring an economic downturn, the federal deficit is apt to stabilize or even modestly fall further relative to GDP.

For that reason, as well as the strong likelihood that falling inflation will enable the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates this year and next, government bond yields are likely to fall irrespective of who is elected president and which party controls Congress.

Implications for capital markets

From a macroeconomic, fiscal or monetary policy perspective, therefore, it is difficult for us to conclude that the choice of US president or the change in majority control in Congress (if any) will have a material impact on variables such as growth, aggregate profits or interest rates—key factors that drive overall capital market returns.

That is not to say, however, that risk premiums will remain low. A contested election, much less a constitutional crisis, would presumably have significant short- and possibly longer-term implications on how domestic and international investors assess US country risk. Should divided government in 2025 lead to the recurring threat of government shutdowns and a potential default, that too would have adverse impacts on risk assessment.

But to the extent that the elections impact investment decisions, it is more likely to be in sector and industry outcomes. A “clean sweep” by Trump and the Republicans, for example, will likely benefit many of today’s more heavily-regulated sectors, such as finance, health care and carbon energy (oil, coal and gas). Alternatively, beneficiaries of a “clean sweep” by Biden and the Democrats could include alternative energy and infrastructure sectors.

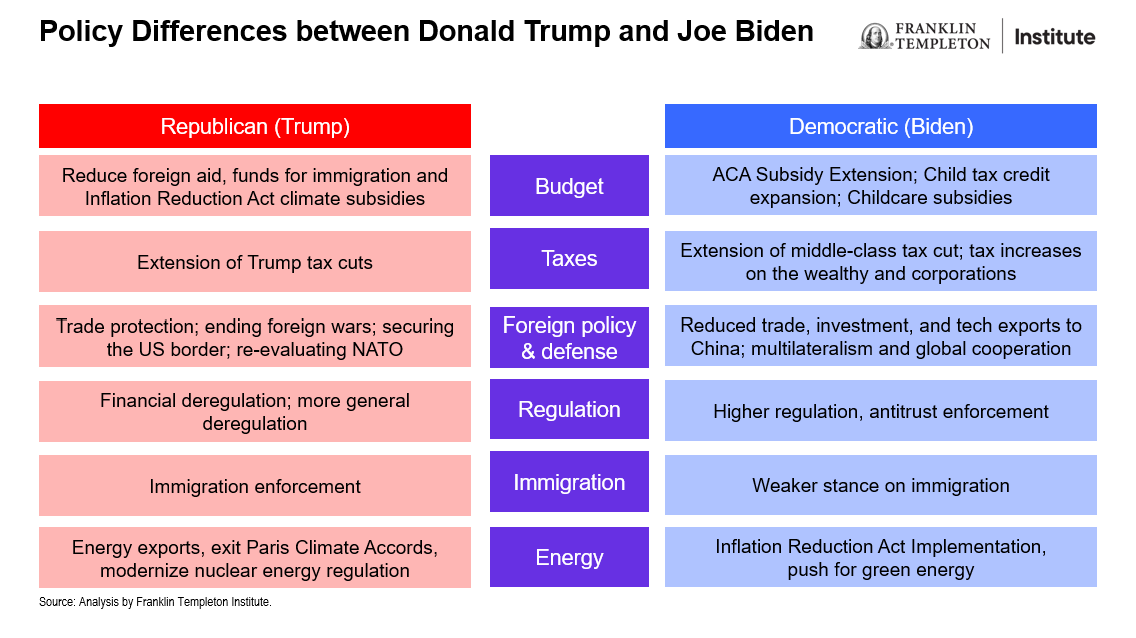

We are not persuaded that performance under past partisan outcomes in Washington (see Exhibit 2 below) will be useful guides for investors today.

Exhibit 2: Equity Market Performance and Election Cycles Since 1932 (right click on chart to enlarge)

Both parties have changed significantly from what they were even as recently as a decade ago, much less several decades ago. A larger proportion of the Republican Party’s voter base is “blue-collar,” lower-income, less-educated segments of the population—cohorts generally less interested in deregulation, tax cuts, free trade or fiscal and monetary policy orthodoxy than the typical Republican voter under Eisenhower or Reagan. The Democratic Party has enjoyed greater support from college-educated “elites,” including in business, finance and technology, and has become more pluralistic than its working-class origins in the 1930s or 1940s. Accordingly, its policies are no longer as “anti-business” as was once commonly believed.

Moreover, the current high equity-market valuations (above long-term norms) and earnings (higher than long-term averages) suggest that overall equity market returns are likely to be lower over the next 5-to-10 years than they have been over the first quarter century of this millennium. The party or parties in power could make matters worse or perhaps better, of course, but the prospects for sustained strong equity gains may not be favorable no matter who wins.

In our examination of the three years before the Trump presidency, the first three years of President Trump’s term, and the first three years of President Biden’s term, a few key conclusions emerge about the present environment:

- Starting valuations for the equity and credit markets are higher.

- Interest rates are at a much higher starting point.

- Earnings expectations are higher, while GDP expectations are lower.

- Consumer confidence is lower.

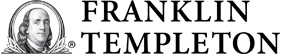

What does this say about the prospects for markets in the runup to the November elections? If history is anything to go by, equity returns during election years have been subdued (Exhibit 3). That strikes us as reasonable, both because the outcome is likely to hang in the balance, and also given the very strong performance of markets over the past 12 months. At some point, we believe some consolidation is warranted.

Exhibit 3: The US Markets and Elections (right click on chart to enlarge)

The bond market could do better, but that may have less to do with the election than the likelihood that receding inflation amid moderating growth will enable the Federal Reserve (Fed) to cut interest rates from mid-2024 onward. And—to anticipate the question—no, we do not believe the Fed will be dissuaded from taking the appropriate monetary policy decisions because of the election. The Fed retains its independence and will do what it feels is consistent with its mandate.

With the notion that there may be difficulty in garnering support for any substantive policy directives given the current environment and the shifting policy positions of each party, we think it would be more effective to focus on fundamentals around where we are in the economic and investment cycle. Our research shows that fixed income looks particularly attractive as interest-rate policy shifts away from a tightening bias. At the same time, many large-cap equities outside the “Magnificent Seven” (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA and Tesla) are showing earnings expectations that exceed market averages at what we consider to be more attractive valuations. If there is one place to consider using the election results as a factor in security selection, sector bias may provide the most opportunity, in our view. We will continue to monitor the path of this election cycle and share our thinking as it evolves.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Equity securities are subject to price fluctuation and possible loss of principal. Fixed income securities involve interest rate, credit, inflation and reinvestment risks, and possible loss of principal. As interest rates rise, the value of fixed income securities falls.

Any companies and/or case studies referenced herein are used solely for illustrative purposes; any investment may or may not be currently held by any portfolio advised by Franklin Templeton. The information provided is not a recommendation or individual investment advice for any particular security, strategy, or investment product and is not an indication of the trading intent of any Franklin Templeton managed portfolio.

IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realized. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

CFA® and Chartered Financial Analyst® are trademarks owned by CFA Institute.

____________

1. Source: “What is the difference between discretionary spending and mandatory spending?” Bookings. July 11, 2023.

English

English 简体中文

简体中文