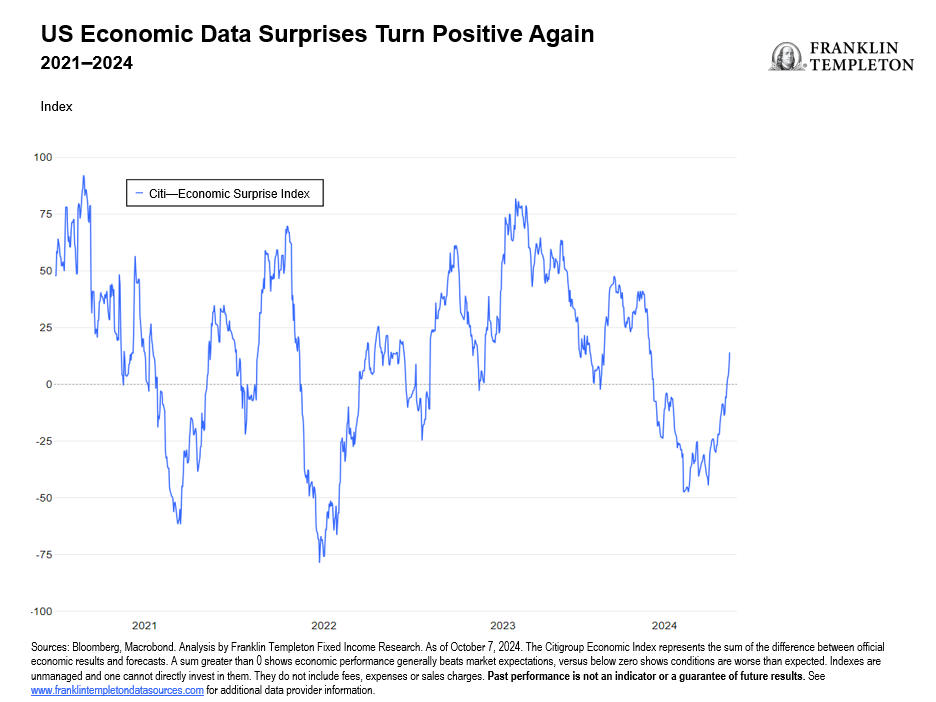

The latest US employment report provided an unequivocal verdict: The labor market is still strong, as Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair Jerome Powell stressed in the September press conference. Nonfarm payrolls blew past expectations, with over 250,000 jobs created in September and upward revisions to previous months. The unemployment rate edged back down to 4.1%, which by most estimates is below the natural rate. The participation rate remained constant, so lower unemployment reflects more people getting jobs, not dropping out of the labor force. Wage growth also exceeded expectations, and the three-month moving average is running at 4.3%, too high for the Fed’s 2% inflation target. This comes after macroeconomic data surprise indices had already turned positive again.

The repeated demonstrations that the economy remains stubbornly resilient have opened a more two-sided debate on the level of the neutral policy rate. I expect that more market observers will gradually come around to my long-held view that this monetary policy easing cycle will likely be short and shallow, because the current policy setting is not overly restrictive to start with.

I thought a 25 basis-point (bp) rate cut in September would have been enough, and this latest data seem to confirm it. The Fed decided to cut 50 bps—which was not the end of the world, of course. The problem, I warned, was that markets risked getting ahead of themselves, pricing another full 50 bps for the remainder of the year. Now it looks quite possible that the Fed will instead decide to hold rates at one of the two remaining policy meetings for 2024, delivering only an extra 25 bps. The reason, I believe, is that it’s becoming increasingly clear that the need and the scope for further monetary easing is limited.

Let’s take a step back. When inflation started rising over three years ago, I argued against the consensus view that we faced just a “transitory” spike entirely driven by supply shocks. I thought there were more durable pressures at work, including very loose financial conditions and an extremely expansionary fiscal policy, both feeding excess demand.1 When the Fed finally started raising rates in March 2022, after inflation had doubled to about 8%, I thought that the planned tightening (less than three percentage points [pp] based on the “dots,” starting from a zero fed funds rate) was nowhere near enough to address the inflation challenge.2 Indeed, the fed funds rate has peaked at 5.25%-5.50%, over 2.5 pp above what the Fed envisaged.

The inflation surge had brought a crucial message: The period of zero interest rates and low inflation that started with the global financial crisis (GFC) and extended through the COVID-19 pandemic was not a new normal: it was an historical anomaly that had come to an end.3 It was time to switch gears and reset our expectations for a world heading back to the pre-GFC norms.

My long-held view on the outlook for policy rates and market yields rests on two pillars, as I discussed in detail in August of last year.4 The first is that the neutral rate of interest is probably somewhere north of 4%, in line with the long-term average preceding the GFC, implying a fair value for longer- term US Treasury yields of 5.0%-5.5%. The second is that loose fiscal policy continues to fuel demand and sets the conditions for future upward pressure on bond yields, through steadily increasing government financing needs.

Over the past year, Fed policymakers have been gradually acknowledging that the neutral rate is higher than they thought. Back in July 2022, after lifting the fed funds rate to 2.25% Powell argued that at 2.25% the fed funds rate had reached its neutral range—needless to say, I strongly disagreed.5 Now the Fed’s median forecast for the natural policy rate is 2.9%, and the upper end of their forecast range (2.4%-3.9%) is very close to my estimate.

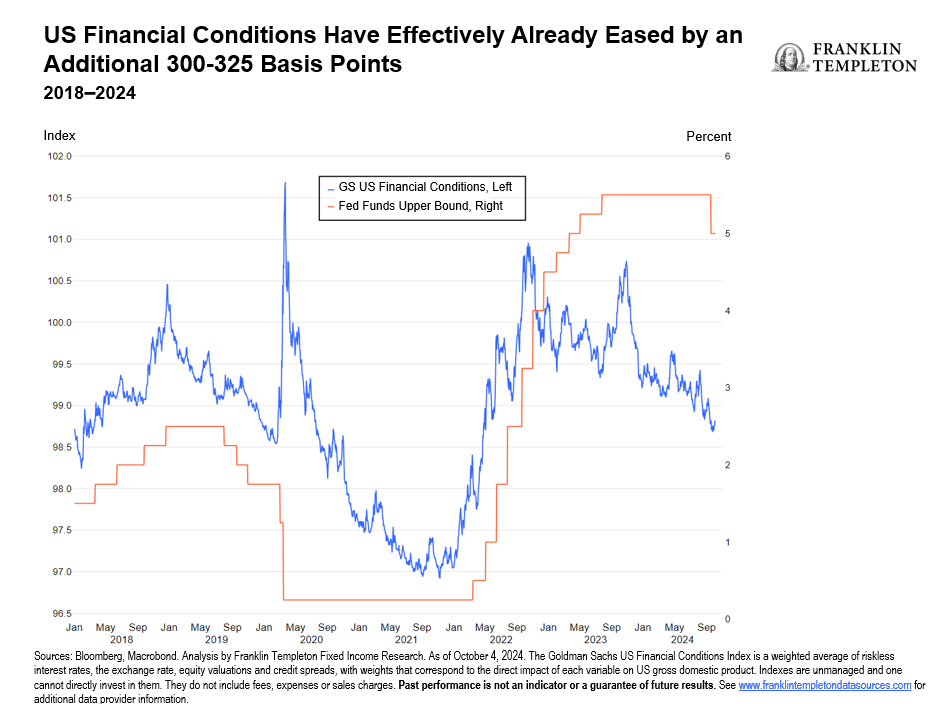

But with the Fed indicating that policy rates would eventually revert to very low levels, at every weak data release financial markets have repeatedly anticipated a significant monetary easing, pushing asset prices up. The resulting easing in financial conditions offset much of the policy tightening effort, turning the Fed into a modern Sisyphus. This problem continues today— financial conditions currently are as loose as when the fed funds rate was at just at 1.5%-1.75% in early-2018 and late-2019.

I am sticking with my call that we should expect just a short and shallow rate-cutting cycle. If the natural policy rate is at least 4%, as I believe, then the current level of 4.75%-5.00% is not very restrictive, particularly given loose financial conditions and very expansionary fiscal policy. (And confirmed by an economy that keeps growing above its potential rate and above full employment.)

The Fed may well decide to keep rates on hold at one of the next two meetings. The next inflation release could be crucial in this respect. While disinflation progress looks well entrenched and the Fed has expressed greater confidence that it’s on track to meet its target, inflation isn’t dead yet—the core Consumer Price Index has been running at 3.3% on average for the last three months, with the core personal consumption expenditures deflator at 2.7%. Wage growth remains robust and given the recent trends in labor market and economic activity, the risk that inflation might settle around 3% is not insignificant. As I said, the next inflation number will provide an important signal. For now, the latest job numbers suggest that we should not exaggerate labor market concerns.

Financial markets will likely continue to anticipate and push for a much deeper monetary easing than what I’m forecasting. If I am right, we are in for a prolonged roller-coaster ride of market volatility.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Fixed income securities involve interest rate, credit, inflation and reinvestment risks, and possible loss of principal. As interest rates rise, the value of fixed income securities falls. Low-rated, high-yield bonds are subject to greater price volatility, illiquidity and possibility of default.

IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realized. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information, and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Issued in the U.S.: Franklin Resources, Inc. and its subsidiaries offer investment management services through multiple investment advisers registered with the SEC. Franklin Distributors, LLC and Putnam Retail Management LP, members FINRA/SIPC, are Franklin Templeton broker/dealers, which provide registered representative services. Franklin Templeton, One Franklin Parkway, San Mateo, California 94403-1906, (800) DIAL BEN/342-5236, franklintempleton.com.

Please visit www.franklinresources.com to be directed to your local Franklin Templeton website.

Copyright © 2024 Franklin Templeton. All rights reserved.

__________

1. See “On My Mind: The UBI-quitous Inflation Question,” June 9, 2021.

2. “To bring inflation under control, in my view, the Fed will need to implement a much more aggressive policy tightening than it currently envisions,” I wrote in “On My Mind: The Fed takes the Red Pill” March 23, 2022.

3. “On My Mind: (r)-stargazing”, June 5, 2024.

4. “On My Mind: The structural shift that wasn’t” August 23, 2023

5. ”On My Mind: Are we there yet?” July 27, 2022).

English

English 简体中文

简体中文