This promises to be quite a challenging year for investors. I think macro uncertainty is especially high, and it might be wise to approach 2024 with even greater intellectual humility than usual.

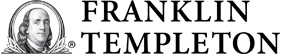

Early in 2023, with the federal funds rate at 4.25%-4.50%, markets expected that before the end of the year the Federal Reserve (Fed) would have reversed course and cut rates by 50 basis points (bps). I felt very strongly that investors were underestimating the inflation problem and the Fed’s determination to deal with it. The Fed did not cut rates, and the fed funds rate today is a full percentage point higher than a year ago.

As the new year kicks off, I feel less out of sync with market consensus, but I believe many investors have again gotten carried away by dovish enthusiasm. The 75 bps in rate cuts the Fed has signaled for this year appear realistic given the progress in inflation, but markets began at some point pricing in close to 150 bps and see the cuts beginning as early as March, which to me seems way too soon. The markets have already done a lot of easing for the Fed, bringing financial conditions back to the level prevailing when the fed funds rate was just 1.75%. With the economy still robust, there should be no hurry for the Fed to cut, though it’s hard to foresee if and how the election calendar might affect the rate-cuts calendar.

If a year ago I was struck by how badly markets seemed to be misreading the Fed, today I am struck by the Fed’s newfound lack of prudence. In December, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell took a victory lap. This is perhaps understandable, because we have seen a substantial decline in inflation with almost no damage to the economy. But the marked change in Fed rhetoric has predictably fueled market conviction that we are about to go back to the happy days of extremely low interest rates and abundant liquidity—a conviction bolstered by the Fed’s signaling that it intends to end quantitative tightening with a much larger balance sheet than previously thought, so as to maintain “more than ample liquidity.”

Whether advertently or inadvertently, the Fed has fueled a new surge in irrational exuberance in markets, which I think contributes to keeping inflation risks alive and makes investing in 2024 a lot more challenging. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t mean to downplay the Fed’s success in bringing inflation under control. Decisive monetary tightening, combined with fading supply shocks, has substantially slowed price dynamics and helped restrain inflation expectations. But there are still two kinds of inflation risks that investors need to be mindful of: first, that the “last mile” back to 2% might prove too slow for comfort; and second, that an ill-timed new shock might send inflation back up.

December Consumer Price Index (CPI) data have just confirmed that inflation remains sticky well above target. Core CPI came in at 3.9% year-over-year (y/y), barely below November’s 4.0%; “supercore,” which excludes shelter as well as food and energy, also held at 3.9% y/y; headline CPI rose to a higher-than-expected 3.4% y/y (from November’s 3.1%). More recent annualized moving averages are only a little lower: 3.3% for core CPI over the last three months, showing no improvement over the past six months.

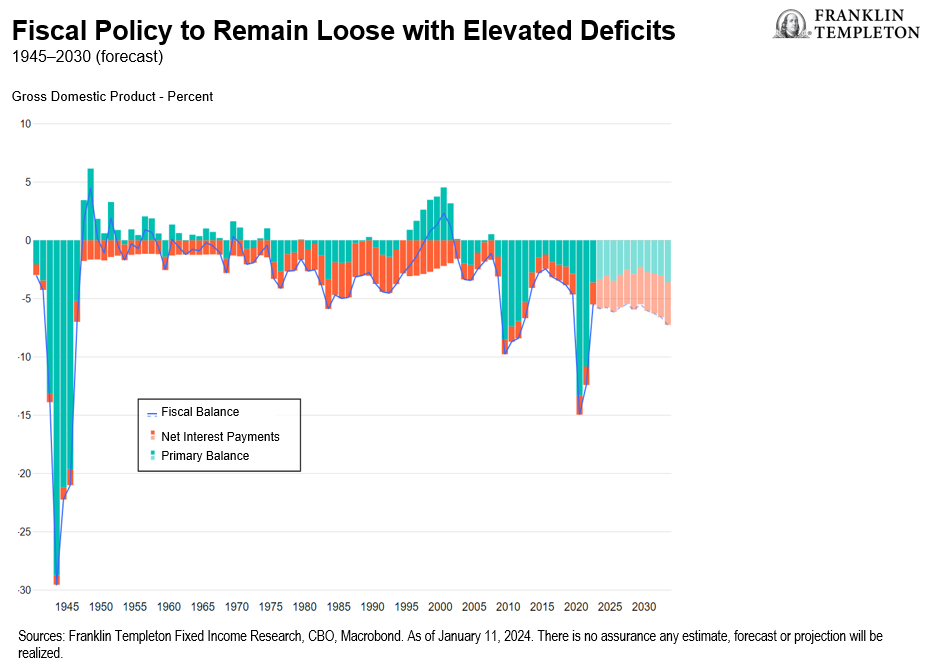

Fiscal policy is the elephant in the room—it remains extremely loose, and as we are entering an election year, I see very little chance of a near-term correction. This not only contributes to inflation risks, but also bolsters the risk of fiscal dominance; it gets increasingly hard for the Fed to ignore the persistently large government financing needs, and the heavier impact that interest expenditures have on the budget itself.

Long-term considerations will also influence the investment environment in 2024, given that we are exiting the inflation emergency period and starting to converge to a new equilibrium. I still believe that the new normal will be a lot like the old normal, the pre-global-financial-crisis (GFC) normal. In other words, I do not believe we will go back to extremely low interest rates and extremely abundant liquidity.

It seems increasingly clear, in my opinion, that the neutral rate of interest is higher than markets think and than the Fed keeps indicating. It is hard otherwise to understand how the US economy has remained so strong even with the fed funds rate above 5% since last May. I think the natural rate, in nominal terms, is likely 4% or a bit higher, rather than the 2.5% in the Federal Open Market Committee’s long-term projections.

The Fed’s signaled intention to keep the balance sheet extremely large also concerns me somewhat. I see many people arguing that the level of reserves at the central bank has nothing to do with bank lending. I think there is a major confusion here. It is true that an expansion in the Fed balance sheet does not automatically force banks to lend more, but it is equally true that a large stock of reserves, which corresponds to a large Fed’s balance sheet, creates ample room for more lending and borrowing should banks choose to do so. It is also true that a large balance sheet through its impact on liquidity contributes to loose financial conditions. This, after all, is exactly why the Fed had launched quantitative easing in the first place. There might be several reasons for the Fed to prefer a larger balance sheet (fiscal dominance and financial repression being possible contributors), but I think it is a risky move. By leaving ample room for lending and borrowing, it opens another channel for more volatile adjustments in the economic and financial system—and it reinforces the market’s view that the post-GFC conditions of ample liquidity will reestablish themselves.

As I look at a US economy which enters 2024 on a strong footing, supported by strong equity markets, loose fiscal policy and a robust labor market with wage growth still well in excess of the inflation target, my conclusion is that this in no way warrants a return to the very loose monetary policy that markets still wish for.

All this makes for a very challenging investment environment, because markets have run well ahead of the Fed, they have already pre-empted more than all the monetary policy action that we can realistically expect this year. So I expect more volatility in the coming quarters, with the 10-year Treasury yield possibly going back toward 4.50%. In the coming quarters, extending duration will start looking more attractive. In my view, fixed income will more firmly reestablish its role as a portfolio diversifier, eventually benefiting from reduced volatility once the Fed’s reaction function becomes less of a focus for markets.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Equity securities are subject to price fluctuation and possible loss of principal.

Fixed income securities involve interest rate, credit, inflation and reinvestment risks, and possible loss of principal. As interest rates rise, the value of fixed income securities falls. Low-rated, high-yield bonds are subject to greater price volatility, illiquidity and possibility of default.

IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realized. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.