The Federal Reserve (Fed) finally acknowledged that high inflation is not transitory—but markets believe its resolve to fight it is.

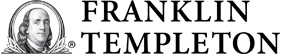

It was high time for the Fed to recognise we have an inflation problem on our hands. Already with the June release, when US Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rose above 5%, I had noted that significant price increases were not limited to a few outliers but had spread to several goods and services categories.

Since then, it’s become even clearer that inflation pressures are broad-based and not just due to base effects: core CPI reached 4.6% year-over-year (Y/Y) in October and has been at or above 4% for five consecutive months. Alternate measures of inflation like the San Francisco Fed’s Cyclical Core PCE and the New York Fed’s Underlying Inflation Gauge have also risen sharply.1 Headline inflation jumped to a 31-year high of 6.2% Y/Y.

Over a year ago, we at Franklin Templeton Fixed Income were already an outlier with our significantly above-consensus inflation call. Four months ago, I again flagged the risk that markets and policymakers might still be underestimating inflation, and I pointed to two factors: the likelihood that high inflation would show a significant degree of inertia, and the dichotomy between consumers and businesses, who expected inflation to persist, and most financial investors who appeared convinced it would not.

Inflation inertia is now baked in the cake. Suppose that the inflation reading for November drops back to 0.2% month-over-month (M/M)—the 2017-2019 average—and stays there. Y/Y inflation will still remain above 6% until next February, and average 5.5% in the 12-month period through May 2022. And that now seems like a best-case scenario, because M/M inflation has averaged 0.6% since the beginning of the year.

Suppose that M/M inflation remains at 0.6% for a while longer, let’s say another six months—remember, it’s already averaged 0.6% for the past 10 months. In that case, Y/Y inflation would rise above 7% in December, peak at close to 8% in February-March, and only drop below 5% a year from now. What’s more, inflation would average 5.4% over a full two years, 2021-2022.

The longer inflation stays in the 5%-6% range, the more it changes the behaviour and expectations of consumers and producers. The anecdotal evidence is piling up: companies are getting used to being charged higher input prices and to charging higher prices for their products—that’s a regime shift from the last many years. Workers are negotiating higher wages with labour demand still outstripping supply. By the middle of next year, these behaviour changes will have become even more ingrained.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has finally acknowledged it’s time to retire the “transitory” moniker. First in a recent speech and then testifying to Congress, he conceded that “transitory” can mean different things to different people. Indeed. Does it mean a few months? A few quarters? A few years? He said that for the Fed it means that “it will not lead to permanently or very persistently higher inflation”. Well, nothing in life is permanent, and “very persistent” is also rather ambiguous. Would one year of inflation above 5% qualify? Because that’s already looking like a best-case outcome, as I noted above.

In a recent seminar, Powell also admitted that the Fed’s “patient” approach might not be a perfect match for an environment of sustained supply bottlenecks and energy price increases, and for the first time he sounded more concerned about inflation than about unemployment.2

Markets took notice and got nervous, and the five-year breakeven rate rose well above 3%.

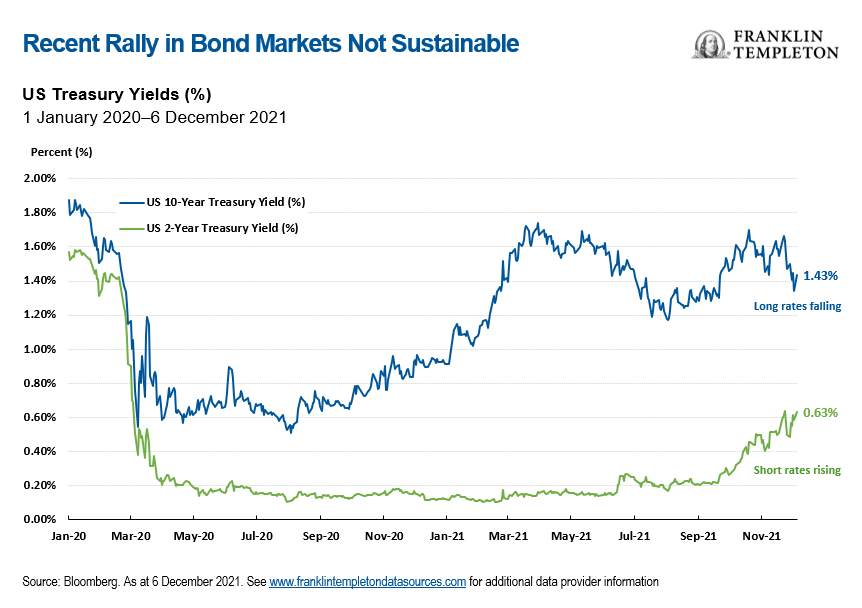

Then news of the COVID-19 Omicron variant broke, and markets quickly scaled back down their expectations of Fed tightening. To some, this feels like 2018, when Powell signalled a tougher monetary stance, the markets balked and the Fed blinked.

There’s a big difference, though. In 2018, inflation was running in a 2%-3% range; today it’s above 6% and likely to stay in a 5%-6% range for a while, as I argued above.

Several countries have re-imposed some COVID-related restrictions as a precaution, but we have no evidence at this point that the Omicron variant will plunge the global economy back in full-scale lockdown.

Markets seem to be betting that the Fed will want to take its own precautions and keep monetary support going as insurance against the downside risks to growth. After all, that’s what the Fed has promised and done over much of the past decade: with inflation risks always low, it focused on growth risks. This time, however, inflation is not just a risk, it’s a reality—a clear and present problem. And if the Fed holds off on tightening, it’s going to get worse. If the Fed does not tighten with inflation running at 5%-6%, inflation expectations will likely get even more unanchored.

Equally important, inflation has now become a serious political liability for the Biden administration. The longer consumers face rising prices, the more dissatisfied they become with the state of the economy. This translates into lower approval ratings for the administration and rising political pressure to bring inflation under control—and this pressure spills over onto the Fed.

Because of these important differences with 2018, I do not believe that the recent strong rally in bond markets can prove sustainable. Unless a new global recession really hits, because of Omicron or another unexpected shock, the bond market is likely underestimating the inflation problem, and underestimating the constraints the Fed now faces.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Investments in lower-rated bonds include higher risk of default and loss of principal. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. Changes in the credit rating of a bond, or in the credit rating or financial strength of a bond’s issuer, insurer or guarantor, may affect the bond’s value.

Important Legal Information

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realised. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Issued in the U.S. by Franklin Distributors, LLC, One Franklin Parkway, San Mateo, California 94403-1906, (800) DIAL BEN/342-5236, franklintempleton.com – Franklin Distributors, LLC, member FINRA/SIPC, is the principal distributor of Franklin Templeton U.S. registered products, which are not FDIC insured; may lose value; and are not bank guaranteed and are available only in jurisdictions where an offer or solicitation of such products is permitted under applicable laws and regulation.

________________________________________

1. Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

2. Source: BIS-SARB Centenary Conference, 22 October 2021.