The Federal Reserve (Fed) has finally acknowledged the reality of the inflation problem. The uncertainty raised by the Russia-Ukraine war did not stop it from raising rates at its March policy meeting, though it capped this first hike to just 25 basis points (bps). Connecting the “dots” points to an expected total of seven rate hikes this year, and Fed Chair Jerome Powell indicated that quantitative tightening (shrinking the Fed’s bloated balance sheet) will start sooner than expected, likely in May.

This might all sound rather hawkish. I had stressed in previous writings that inflation had become a major social and political problem, and in this month’s press conference, Powell tried to channel former Fed Chair Paul Volcker, signalling the Fed is aggressive and determined to bring inflation under control.

But compared to the magnitude of the inflation challenge, I believe the Fed’s stance is nowhere near as hawkish as it should be—though it sounds very hawkish compared to its previous implausibly accommodative line.

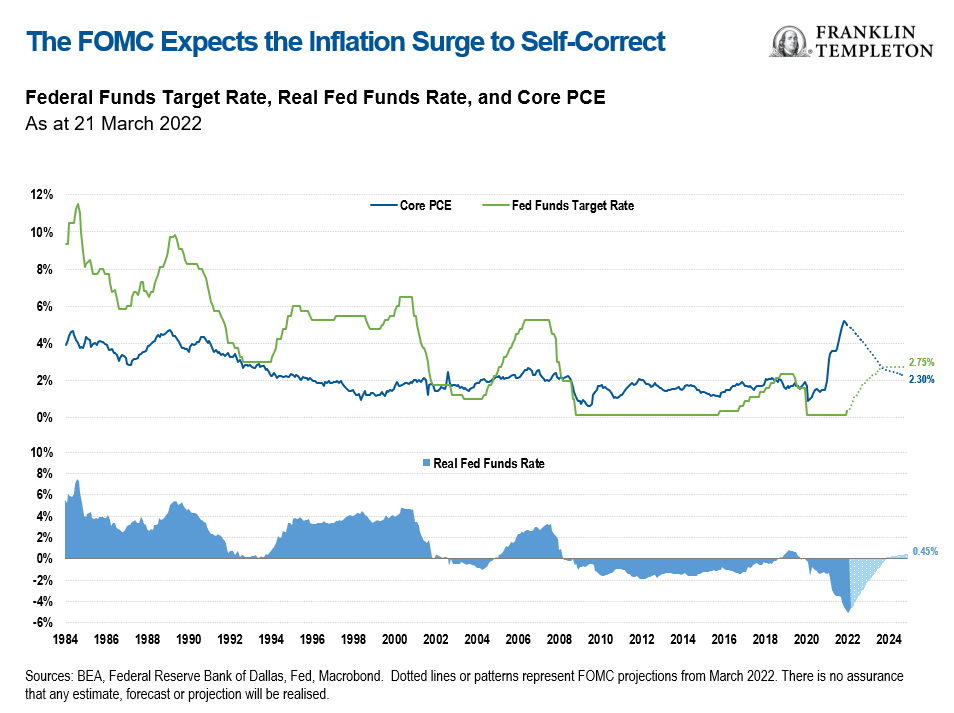

In previous tightening cycles, the Fed has had to lift the policy rate above inflation to bring price dynamics back under control. Today, the policy rate is barely above zero while headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation is close to 8% and the Fed’s preferred core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) measure stands at 5.2%.1 That’s a long way to go, and another six rate hikes—if this includes just one 50 bps bump in a series of predictable 25 bps increments—will leave the policy rate under 2% (the Federal Open Market Committee [FOMC] median projection is 1.875%).

The Fed expects the policy rate to peak at 2.75% in 2023 (median FOMC projection); only then, in the Fed’s view, would the policy rate exceed core PCE, which the Fed projects would drop to 2.6%.

The Fed’s “hawkish” stance, in other words, is mostly wishful thinking. It still assumes that this inflation surge will self-correct and that inflation will come back to target even as the real interest rate remains negative throughout this year and for part of next year as well. In substance, this does not differ that much from the previous mantra that inflation was “transitory”.

Some Unpleasant Inflation Arithmetic

Here is an update of the unpleasant inflation arithmetic that I like to use in my inflation-themed pieces: headline CPI inflation—which is what matters for consumer behaviour and wage-setting—averaged 0.7% month-on-month (M/M) for the last six months, and 0.6% for the last 12. Let’s be optimistic and assume it will average just 0.4% from March through December. Headline inflation would end the year at 5.6%—three times higher than the projected end-year policy rate. Core PCE averaged 0.4% M/M over 2021; if it keeps that pace, it will end the year at 5%. If headline CPI keeps the pace of the last 12 months, it will end the year close to the latest reading, at 7.7%. Real interest rates would remain deep in negative territory.

How can we expect inflation to behave in the coming months? Let’s take the pulse of the underlying macro situation. The US labour market remains extremely tight and cost of living adjustments (COLA), where wages are automatically indexed to past inflation, are making a comeback—because inflation has consistently outstripped policymakers’ and private sector forecasts for too long. The Fed itself expects the labour market to get even tighter, pushing the unemployment rate down to 3.5% (from the current 3.8% in February).

Geopolitical uncertainty has caused energy prices to surge, has put pressure on other raw materials, and has caused further disruptions to supply chains. (As I noted in my last “On My Mind”, the Russia-Ukraine war also marks another retreat from globalisation, and the rising preference for self-sufficiency in key industries will become a significant long-term inflationary factor.) Companies have discovered they have pricing power—and with input costs rising, they have little choice but to exercise it.

In other words, a number of self-sustaining inflationary forces have been set in motion—abetted by the continuation of an exceptionally loose monetary policy that, in combination with a record surge in government spending, has proved to be a major policy mistake (something I believe should have been clear months ago).

To be clear, inflationary supply shocks are playing a role here—but they are certainly not alone. When a supply shock pushes up inflation, a central bank must assess the risk that it will trigger “second round effects”, price and wage increases that will propagate and amplify the shock. Only if this risk is significant should the central bank react and raise rates; otherwise, it should wait for the supply shock to fade. In the current case, extremely loose fiscal and monetary policy had already been fuelling inflation since the post-pandemic recovery started; they are an important source of inflation by themselves, and moreover, they make it inevitable that any supply shock will quickly trigger second round effects that make its inflation push self-sustaining.

To expect that inflation will now come back to target on its own—even if higher prices and geopolitical uncertainty cool off economic activity—is foolhardy.

To bring inflation under control, in my view, the Fed will need to implement a much more aggressive policy tightening than it currently envisions. To see it through, it will most likely need the courage to withstand substantially higher volatility in asset markets, which might include painful corrections. That’s when the Fed’s anti-inflation mettle will be tested. If inflation remains high, its social and political costs will rise even further, and the Fed might have little choice but to tough it out.

The Fed has taken the red pill and seen the inflationary reality we live in; but like Neo in The Matrix movie, it will take longer to fully come to terms with reality—and recognise what it will take to bring inflation under control.

Investment Implications

Financial investors also face challenging times. Markets expect a short hiking cycle, with fed funds peaking at around 2.75%, followed by rate cuts by 2024. Some analysts see this as indicating an early end to the current economic expansion; the flattening Treasury yield curve, which could invert with further rate hikes, would signal an upcoming recession partly due to monetary tightening. I do not think the yield curve currently represents a reliable recession signal because there are other factors at play, especially the massive role the Fed still plays in the market. The 10-year term premium has barely budged even as inflation spiked to 8%, suggesting that long-dated yields are probably still capped by the Fed’s record-high balance sheet. Or maybe investors think the Fed will blink and ease policy again once asset prices start a meaningful correction. In either case, I think markets are still underestimating the magnitude of the monetary policy tightening ahead.

How can fixed income investors position for this challenging environment? Long duration assets could have a volatile and difficult period ahead as rates climb; shorter duration looks more attractive to us. Fixed income investors should also consider asset classes that are naturally aligned to rising rates, such as bank loans. We have now started to see credit spreads widening, and this creates some interesting pockets of opportunity in high yield credit markets. Finally, rising commodity prices imply a stronger outlook for commodity-rich emerging markets, not only in the energy space.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. Investments in lower-rated bonds include higher risk of default and loss of principal. Floating-rate loans and debt securities tend to be rated below investment grade. Investing in higher-yielding, lower-rated, floating-rate loans and debt securities involves greater risk of default, which could result in loss of principal—a risk that may be heightened in a slowing economy. Interest earned on floating-rate loans varies with changes in prevailing interest rates. Therefore, while floating-rate loans offer higher interest income when interest rates rise, they will also generate less income when interest rates decline. Changes in the financial strength of a bond issuer or in a bond’s credit rating may affect its value.

Important Legal Information

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or of the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realised. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Issued in the U.S. by Franklin Distributors, LLC, One Franklin Parkway, San Mateo, California 94403-1906, (800) DIAL BEN/342-5236, franklintempleton.com – Franklin Distributors, LLC, member FINRA/SIPC, is the principal distributor of Franklin Templeton U.S. registered products, which are not FDIC insured; may lose value; and are not bank guaranteed and are available only in jurisdictions where an offer or solicitation of such products is permitted under applicable laws and regulation.

CFA® and Chartered Financial Analyst® are trademarks owned by CFA Institute.

____________________________

1. Sources: BEA, BLS. CPI = Consumer Price Index; PCE = Personal Consumption Expenditures